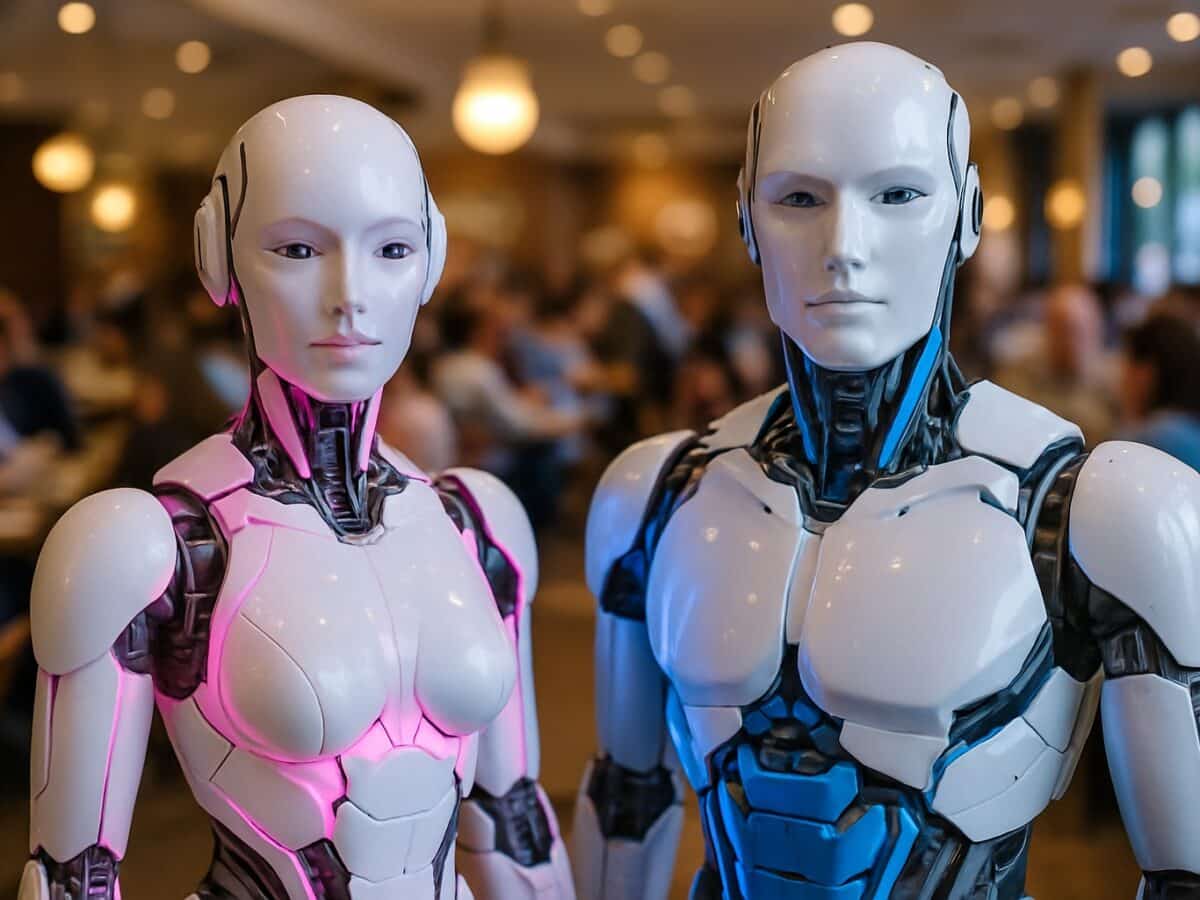

People may be more likely to trust robots based on their perceived gender. (Photo by StudyFinds on Shutterstock AI Generator)

Female Diners More Likely to Trust ‘Male’ Server Bots

In a nutshell

- Powerless women were significantly more likely to trust and follow recommendations from male-like robots over female-like ones, revealing how gender and power dynamics shape human-robot interactions.

- When robots were designed to look cute, using features like round faces and big eyes, these gender biases disappeared, with participants responding equally to both male- and female-like robots.

- The study suggests that robot design choices, including color and facial features, can subtly influence consumer behavior, raising important questions about ethics and inclusivity in the growing service robot industry.

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Would you take menu advice from R2-D2 or C-3PO? Your answer might depend less on their programming and more on whether you perceive them as male or female, and your own sense of social power. New research from Penn State shows we don’t leave our gender biases behind when interacting with machines, a finding that could reshape how restaurants design their increasingly popular robot waitstaff.

The research, published in the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, reveals how deeply gender stereotypes are embedded in our psyche. So deeply, in fact, that we project these biases onto machines with merely gendered appearances.

“Robots can be designed or programmed to have human-like features like names, voices, and body shapes, which portray gender,” says study author Anna Mattila from Penn State, in a statement.

The Robot Revolution in Restaurants

The rise of service robots is no passing trend. According to industry forecasts cited in the study, the service robotics market was valued at $42.8 billion in 2022 and is expected to grow at a staggering 25% annual rate, reaching $425 billion by 2032. Major restaurant chains, including TGI Fridays and Buffalo Wild Wings, have already deployed robots for food delivery, while Pizza Hut has used robots for taking orders and payments.

Many service businesses choose feminine characteristics for their robots. The researchers point to examples like Big Bang Pizza, where robots with feminine names welcome guests, offer recommendations, and provide service. Similarly, a robotic bartender called Cecilia.ai conducts interactive conversations and offers drink recommendations. These robots often feature distinctly feminine names and appearances.

But does this gendered design influence how customers respond to these robots? And could such designs inadvertently reinforce harmful stereotypes?

Gender and Power

In their first experiment, researchers recruited 239 participants from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform. They randomly assigned participants to interact with either a pink “female-like” robot or a gray “male-like” robot, which delivered identical menu recommendations for a breakfast burrito. Participants rated how persuasive they found the robot and how likely they were to accept its recommendation.

The results revealed that powerless women, defined as those who reported feeling less control over their circumstances, found the male-like robot significantly more persuasive than the female-like robot. This bias disappeared completely among powerful women, powerful men, and even powerless men.

The researchers explain that historical labor divisions created enduring power dynamics between genders. Men traditionally held positions with greater authority and decision-making power, while women often occupied subordinate roles. These historical differences appear to influence how powerless women evaluate robot recommendations today.

Perceived persuasiveness mediated the relationship between robot gender and recommendation acceptance. In other words, powerless women weren’t just more likely to accept recommendations from male-like robots—they found them inherently more convincing.

Could Cuteness Be the Solution?

Recognizing the potential ethical concerns of perpetuating gender stereotypes through robotic design, the researchers conducted a second study to explore whether certain design elements could mitigate gender bias.

For their second experiment, the team focused exclusively on college students, who typically occupy low-power positions in social hierarchies. They used Bear Robotics’ Servi robot with an iPad display showing either “male-like” blue facial features or “female-like” pink features. Both designs incorporated characteristics that trigger what psychologists call the “baby schema” effect—round faces, big eyes, small chins and noses—that humans instinctively find cute and trustworthy.

When robots featured these cute, infant-like characteristics, gender bias disappeared entirely. Both male and female participants responded similarly to cute robots regardless of gender cues.

The researchers found that cuteness enhances communal traits that can diminish the authority characteristics typically associated with male figures. This is particularly relevant for male-appearing robots, where cuteness reduced the authoritative traits that might otherwise lead powerless women to find them more persuasive.

Peng said, “For businesses that want to mitigate gender stereotypes, they can consider using a cute design for their robots.”

Designing Robots for Inclusivity

Hotels, retail stores, and other service environments increasingly deploy robots for customer interactions. Designers of these robots must now consider how their gendered features might influence customer responses based on demographics and perceived power.

Rather than choosing between male-like or female-like robots, businesses could incorporate cute features that help neutralize gender biases while preserving the benefits of anthropomorphic design (resemblance to humans). This would allow them to maintain engaging human-robot interactions without reinforcing potentially problematic stereotypes.

Our relationship with technology isn’t purely about the technology itself. We bring our full human complexity, including our biases, to every interaction, even with lifeless machines that merely simulate gender through color and design.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The researchers conducted two separate studies to examine how robot gender affects menu recommendation acceptance. Study 1 used a 2×2×2 design with 239 MTurk participants, manipulating robot gender (male-like vs. female-like), consumer gender (male vs. female), and sense of power (low vs. high). Participants viewed a gendered robot (pink for female-like, gray for male-like) that recommended a breakfast burrito, then rated the robot’s persuasiveness and their likelihood of accepting the recommendation. Study 2 focused only on college students (156 participants) as a low-power demographic, using a 2×2 design with cute robot gender (male-like vs. female-like) and consumer gender (male vs. female). This study used physical Bear Robotics’ Servi robots with iPad displays showing gendered facial features, both designed with “baby schema” characteristics like round faces and big eyes, with the male version using blue and the female version using pink.

Results

Study 1 revealed a significant three-way interaction between robot gender, consumer gender, and sense of power. Powerless women found male-like robots significantly more persuasive than female-like robots and were more likely to accept their recommendations. This gender preference disappeared among powerless men and powerful consumers of either gender. Study 2 showed that when robots were designed with cute features, the gender bias was eliminated—both male and female consumers responded similarly to cute robots regardless of gender signals. The researchers found that cuteness triggered perceptions of warmth and trustworthiness that overrode gender-based differences, particularly for male-like robots where cuteness reduced the authoritative traits that might otherwise lead powerless women to perceive them as more persuasive.

Limitations

The study did not explicitly mention limitations, but some potential limitations include: the use of color as the primary gender manipulation in Study 1, the focus only on restaurant menu recommendations rather than other persuasive tasks, the use of college students to represent low-power individuals in Study 2 rather than manipulating situational power, and the potential limited generalizability of findings to real-world service settings where multiple factors beyond gender may influence customer responses.

Funding & Disclosures

The authors acknowledged funding from the J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation and expressed appreciation to Bear Robotics for providing the robot Servi used in their study. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Publication Information

The paper titled “Gendered robots and persuasion: The interplay of the robot’s gender, the consumer’s gender, and their power on menu recommendations” was authored by Zixi (Lavi) Peng, Anna S. Mattila, and Amit Sharma. It was published in the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management (Volume 62, pages 294-303) in February 2025.