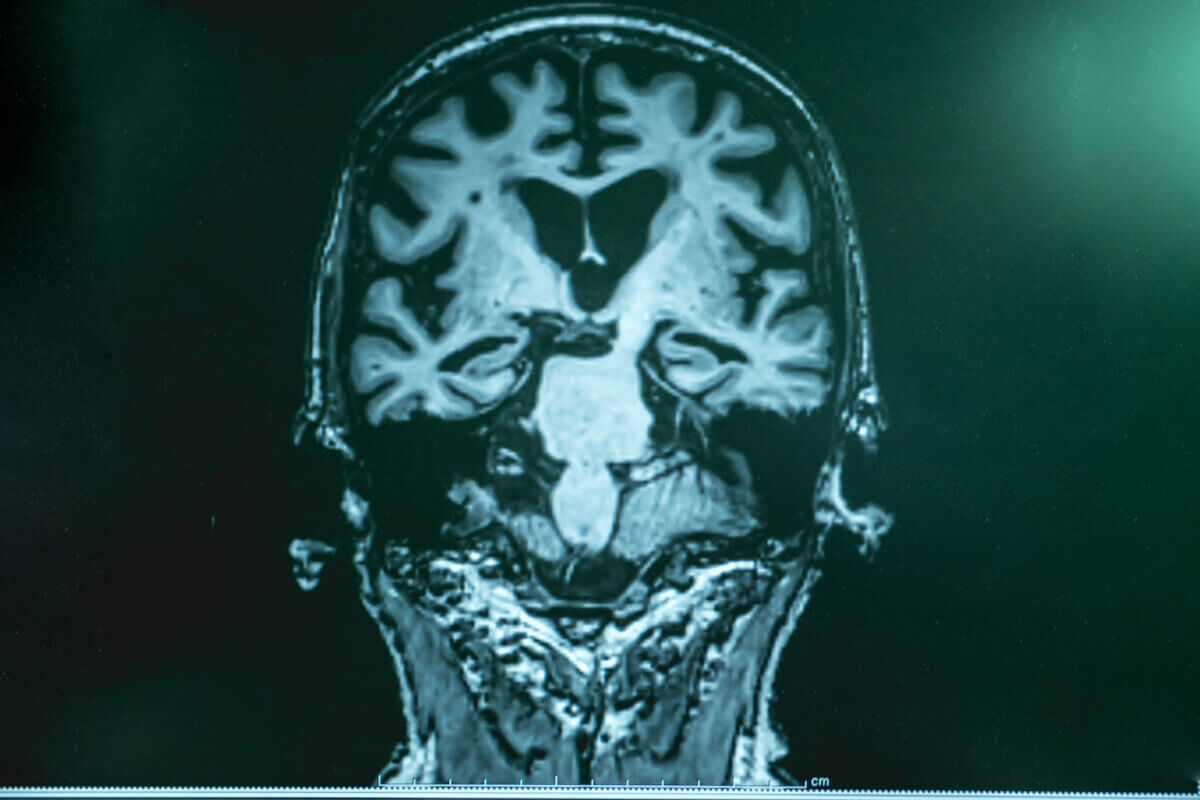

(Photo by Robert Kneschke on Shutterstock)

In a nutshell

- Drugs commonly used to treat HIV and hepatitis B (called NRTIs) were found to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease by 4-13% for each year they were taken

- These medications appear to work by calming inflammation in the brain caused by overactive “alarm systems” called inflammasomes, which are implicated in Alzheimer’s disease

- This discovery offers a potential new approach to Alzheimer’s treatment that targets inflammation rather than just the protein buildups typically associated with the disease

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — A common medication used to treat HIV and hepatitis B may offer unexpected protection against Alzheimer’s disease, according to scientists at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Their study found that people taking these drugs, known as NRTIs, had a significantly lower chance of developing Alzheimer’s – a discovery that could yield brand new treatment approaches for the devastating brain disorder.

The Unexpected Connection

After analyzing health records of more than 270,000 individuals across two major U.S. healthcare databases, researchers discovered that each year a patient took NRTIs corresponded with a 4-13% drop in Alzheimer’s risk. This protection wasn’t seen with other HIV medications, pointing to something unique about how NRTIs work in the body.

The research team, led by Dr. Jayakrishna Ambati, observed this protective pattern consistently across both databases they studied, with the effect becoming stronger the longer patients had been taking the medications. Their paper is published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

For the 6 million Americans affected by Alzheimer’s and their families, this finding offers a new direction. While existing treatments mainly target protein buildups in the brain, NRTIs work differently – they tamp down inflammation, a key driver of brain damage in Alzheimer’s.

How NRTIs Protect the Brain

NRTIs seem to block molecules called inflammasomes, which act like alarm systems in brain cells. In Alzheimer’s disease, these alarms often malfunction, triggering harmful inflammation even when there’s no real threat.

When proteins build up in the brain – a hallmark of Alzheimer’s – they activate these inflammasomes, particularly one called NLRP3. This sets off a chain reaction of inflammation that damages brain cells and accelerates cognitive decline.

The research team has previously demonstrated in laboratory studies that NRTIs can inhibit inflammasome activation through mechanisms independent of their antiviral effects. In this latest study, they examined records from the Veterans Health Administration spanning 2000-2024 and the MarketScan database covering 2006-2020. They focused on individuals over 50 with HIV or hepatitis B diagnoses, comparing those who received NRTIs to those who didn’t.

To ensure fair comparisons, they matched patients with similar characteristics and controlled for numerous factors known to affect Alzheimer’s risk – from age and race to diabetes, heart disease, depression, and brain injuries.

A small clinical trial testing the NRTI lamivudine in Alzheimer’s patients has already shown early promise, with participants showing decreased markers of brain inflammation after six months.

Moving Forward With Caution

These medications aren’t without risks. NRTIs can cause side effects, including rare but serious conditions like lactic acidosis. However, newer generations have fewer side effects, and researchers are developing versions that maintain the brain-protecting benefits without the drawbacks.

One advantage in this line of research is that it focuses on drugs already approved by regulatory authorities for other conditions, potentially accelerating the pathway to new Alzheimer’s treatments compared to developing entirely new compounds.

As our population ages and Alzheimer’s cases increase, this research presents a promising new approach. If further trials confirm these findings, doctors might eventually prescribe NRTIs or similar drugs specifically to prevent or slow Alzheimer’s progression – adding a valuable weapon to our limited arsenal against this condition.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of health insurance claims from two major U.S. databases: the Veterans Health Administration (VA) database covering 2000-2024 and the MarketScan database covering 2006-2020. They identified patients who were at least 50 years old, had been diagnosed with HIV or hepatitis B, and had no prior diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease at the study start. They tracked NRTI medication exposure over time by measuring cumulative years of use based on pharmacy records. To ensure fair comparisons, they used propensity score matching to create patient cohorts with similar baseline characteristics and adjusted for numerous demographic and clinical factors known to affect Alzheimer’s risk. They also conducted a competing risk analysis to account for the possibility that patients might die before developing Alzheimer’s.

Results

The study found that each additional year of NRTI exposure was associated with a 4% reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s in the VA database and a 10.3% reduced risk in the MarketScan database. After propensity score matching and adjusting for potential confounders, the protective effect remained significant with a 6% reduced hazard per year of NRTI use in the VA cohort and 13% in the MarketScan cohort. Importantly, other classes of HIV medications did not show this protective effect. The researchers also conducted subgroup analyses showing similar protective effects in both HIV-positive patients without hepatitis B and hepatitis B-positive patients without HIV.

Limitations

The study acknowledged several limitations. As an observational study using administrative claims data, it could not establish causality. The data lacked information on genetic variants that might increase Alzheimer’s risk. The researchers couldn’t assess Alzheimer’s progression with clinical measures like cognitive assessments. There could also be differences in healthcare access and diagnostic practices between the VA and MarketScan cohorts. Additionally, there might be residual or unmeasured confounding factors despite the researchers’ efforts to control for known variables.

Funding and Disclosures

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the University of Virginia Strategic Investment Fund, the South Carolina Center for Rural and Primary Healthcare, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Dorn Research Institute. Several authors disclosed potential conflicts of interest, including that lead author Jayakrishna Ambati is a co-founder of iVeena Holdings, iVeena Delivery Systems, and Inflammasome Therapeutics, and has served as a board member or consultant for various pharmaceutical companies. Some authors are named as inventors on patent applications related to the research.

Publication Information

The paper titled “Association of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor use with reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease risk” was published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, in 2025. It was received on November 4, 2024, revised on March 11, 2025, and accepted on March 17, 2025. The DOI is 10.1002/alz.70180.