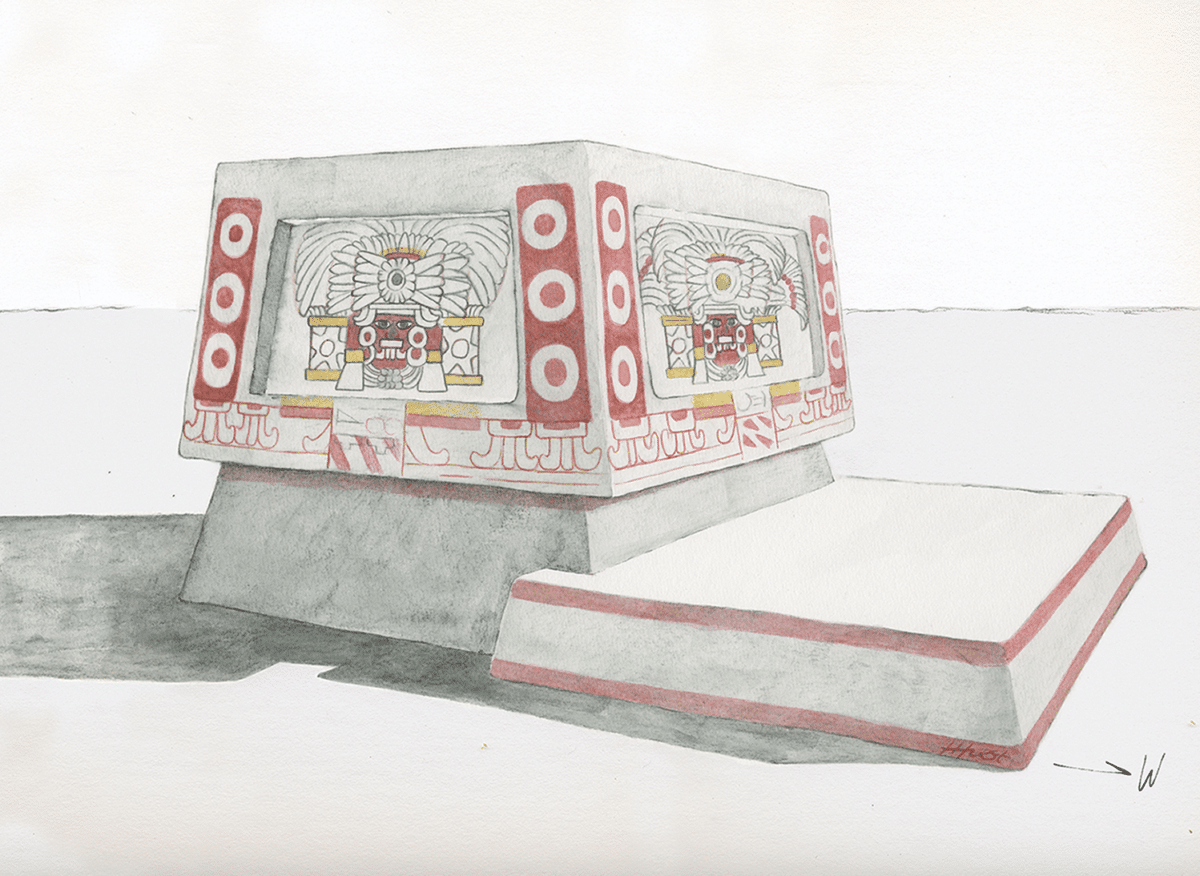

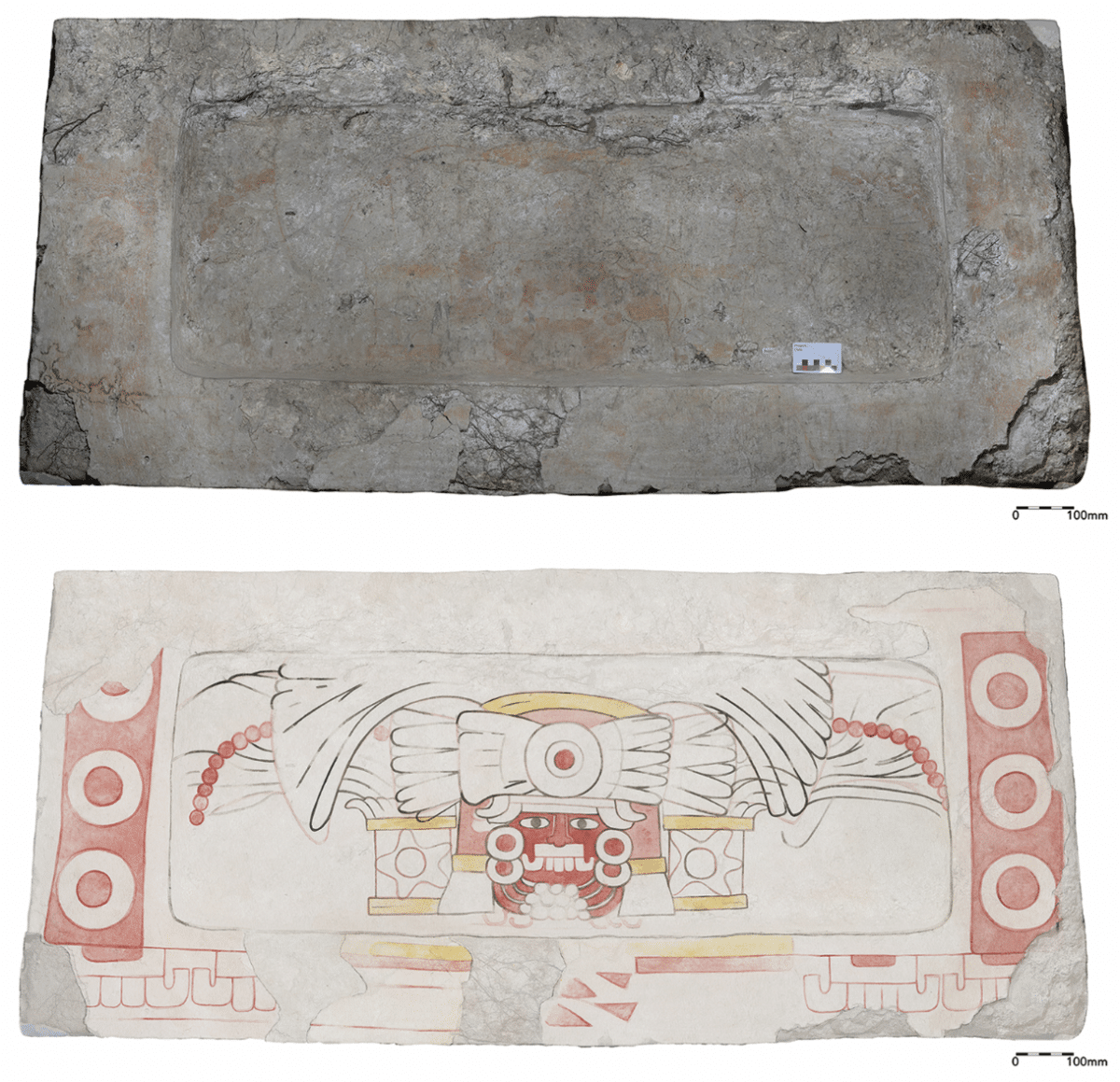

Structure 6D-XV-Sub3, altar found buried under the Mayan city of Tikal with murals photographed from the south-west (Credit: Antiquity/Cambridge University Press; Photograph by E. Román)

In a nutshell

- Archaeologists discovered a 5th-century painted altar at Tikal with undeniable Teotihuacan artistic style, proving people from central Mexico established a physical presence in the Maya city

- The altar features distinctive Teotihuacan architecture, painting techniques, and was surrounded by infant burials consistent with Teotihuacan ritual practices

- This discovery settles decades of debate about Teotihuacan-Maya relations, suggesting a foreign enclave existed at Tikal following the “Entrada” conquest of AD 378

PROVIDENCE, R.I. –– Archaeologists have found a smoking gun in the ancient rivalry between two Mesoamerican powers. A newly discovered painted altar found buried under the Maya city of Tikal bears the unmistakable artistic style of distant Teotihuacan, revealing that people from central Mexico weren’t just trading with the Maya – they were living among them and wielding real power.

For decades, archaeologists have debated the nature of interactions between Teotihuacan (located near modern-day Mexico City) and Maya cities like Tikal in Guatemala. Evidence suggested some form of contact, but the question remained: was this merely trade influence, or something more direct and powerful?

The discovery settles this debate, it seems. This painted altar, dating to the fifth century AD, shows that Teotihuacan artists were working directly in the Maya heartland.

“The altar murals are expert examples of a complex, non-local style and likely evidence of the direct presence of Teotihuacan at Tikal as part of a foreign enclave,” write the international team of researchers in their study, published in the journal Antiquity.

For comparison, imagine finding a perfectly executed Japanese temple in the middle of medieval England, complete with authentic calligraphy and precise architectural details. It would require Japanese builders and artists on site – not just English craftsmen copying foreign styles they’d seen in imported goods.

The altar, designated Structure 6D-XV-Sub3, sits at the center of a residential compound in Tikal’s southern sector. Though small (just 1.8 × 1.33m and 1.1m tall), it packs tremendous historical significance. The structure features the distinctive “talud-tablero” profile characteristic of Teotihuacan architecture and previously unknown in the Maya region before contact with central Mexico.

Each side displays the frontal image of a deity with a feathered headdress, fanged mouthpiece, and flanking shields. The researchers note these figures resemble what’s often described in central Mexico as the “Storm God,” with variations in color suggesting they represent deities associated with the four cardinal directions.

The artistic style matches painting techniques documented at Teotihuacan itself: preparatory drawing, heavy contour lines, layered pictorial planes, and rigid bilateral symmetry. Everything from the execution to the subject matter screams Teotihuacan, not Maya.

“It’s increasingly clear that this was an extraordinary period of turbulence at Tikal,” says co-author Stephen Houston, a professor of social science, anthropology, and history of art and architecture at Brown University, in a statement. “What the altar confirms is that wealthy leaders from Teotihuacan came to Tikal and created replicas of ritual facilities that would have existed in their home city. It shows Teotihuacan left a heavy imprint there.”

Edwin Román Ramírez of the Proyecto Arqueológico del Sur de Tikal led the team that made this remarkable find after lidar surveys in 2016 revealed previously unknown structures. The altar came to light during excavations of Group 6D-XV, a residential compound that had been intentionally buried around AD 550-645.

The timing aligns perfectly with historical texts that mention a conquest of Tikal by Teotihuacan in AD 378 – an event scholars call the “Entrada” or “Arrival.” The altar and its containing compound were built and used during the following century, when Teotihuacan influence was at its peak..

Around the altar, archaeologists found infant burials and evidence of burning rituals that match practices documented at Teotihuacan. The compound was eventually buried after a ceremony that left burnt material spread over 3 meters, with radiocarbon dating suggesting this occurred between AD 550-645 – roughly when Teotihuacan itself began to decline.

“This departure from the hybridity of other examples” where Teotihuacan and Maya elements mix, notes the research team, shows “Structure 6D-XV-Sub3 incorporates Central Mexican artistic practice, aesthetics and offerings.”

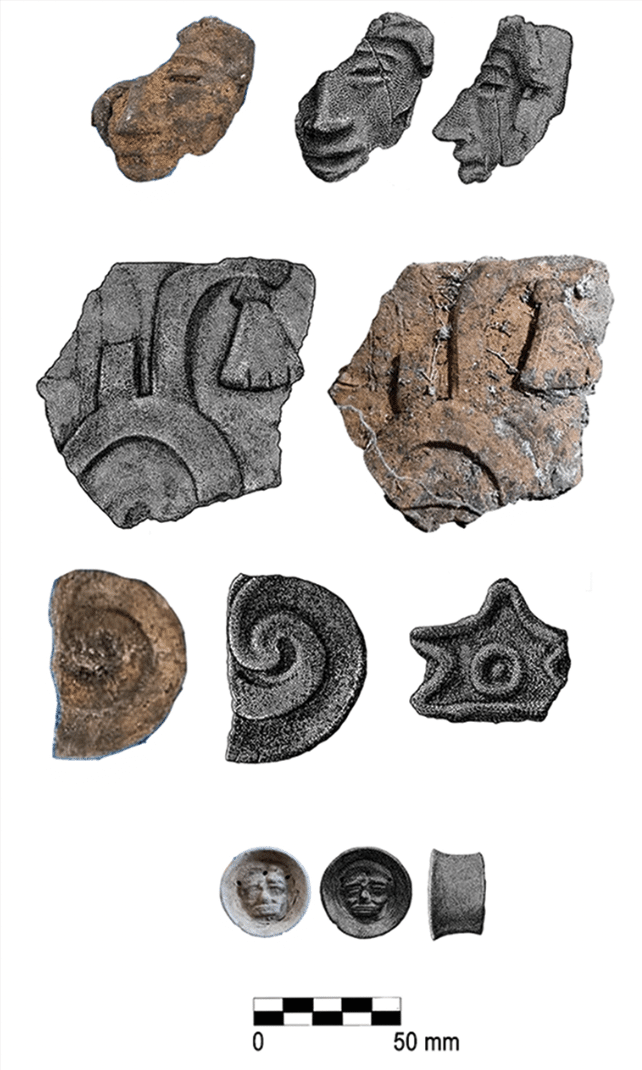

The altar discovery joins other Teotihuacan-linked finds in Tikal’s southern sector, including a complex called Group 6D-III that resembles a miniature version of Teotihuacan’s “Ciudadela” (Citadel) complex. Excavations there yielded over 5,000 fragments of incense burners that were locally produced but Teotihuacan in style.

Additionally, dart points recovered from excavations were “probably crafted at Teotihuacan or by people trained at the metropolis,” according to expert analysis cited in the study.

Beyond simply confirming Teotihuacan presence at Tikal, the altar’s existence helps explain the power dynamics between these ancient superpowers. Rather than peaceful cultural exchange, we now have physical evidence of what was likely a foreign enclave established after military conquest – a potential ancient colony nestled within one of the most powerful Maya cities.

By looking closely at this remarkable find, we’ve uncovered the footprint of an ancient foreign occupation that marked a turning point for Maya civilization.

“Everyone knows what happened to the Aztec civilization after the Spanish arrived,” Houston says. “Our findings show evidence that that’s a tale as old as time. These powers of central Mexico reached into the Maya world because they saw it as a place of extraordinary wealth, of special feathers from tropical birds, jade and chocolate. As far as Teotihuacan was concerned, it was the land of milk and honey.”

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers from the Proyecto Arqueológico del Sur de Tikal conducted excavations at Group 6D-XV at Tikal, Guatemala, after lidar surveys in 2016 revealed previously unknown structures in the area. They uncovered a residential compound with a central painted altar (Structure 6D-XV-Sub3) that displays distinctive Teotihuacan characteristics. The team documented the altar using photogrammetry and enhanced the faded paintings with dStretch software, which uses decorrelation stretch algorithms to make faint pigments more visible. They also collected samples for radiocarbon dating to establish the chronology of the structure and surrounding complex.

Results

The excavations revealed a small talud-tablero altar with paintings on all four sides that display frontal deity figures with features consistent with Teotihuacan artistic conventions. The altar was surrounded by infant burials and evidence of ritual burning, practices also documented at Teotihuacan. Radiocarbon dating placed the residential compound to the fifth century AD, with a range of cal AD 360-540 for the construction of the buildings around the altar. The complex was eventually buried after a ceremony that occurred between cal AD 550-645. Beyond the altar itself, researchers found other Teotihuacan-related objects, including a ceramic drum-shaped earspool that is unique to the Maya area but common at Mexican sites affiliated with Teotihuacan.

Limitations

The researchers note that the precarious condition of the murals meant they could not excavate within the altar structure, limiting their understanding of its construction details. Additionally, while the evidence strongly suggests Teotihuacan artists created the altar, they acknowledge they cannot definitively determine whether it was made by Teotihuacan artists at Tikal or by Maya artists thoroughly trained in Teotihuacan style, especially since Teotihuacan itself had artists who were literate in Maya writing.

Funding

The excavations and research were funded by PACUNAM-Fundación Patrimonio Cultural y Natural Maya and the Hitz Foundation. Additional support for radiocarbon dating came from Brown University’s Dupee Family Professorship of Social Sciences, with travel support from Skidmore College and the University of Texas, Austin.

Publication Information

The study “A Teotihuacan altar at Tikal, Guatemala: central Mexican ritual and elite interaction in the Maya Lowlands” appears in Antiquity (Volume 99, Issue 404, pages 462-480), published in 2025. Authors include Edwin Román Ramírez, Lorena Paiz Aragón, Angelyn Bass, Thomas G. Garrison, Stephen Houston, Heather Hurst, David Stuart, Alejandrina Corado Ochoa, Cristina García Leal, Andrew Scherer, and Rony E. Piedrasanta Castellanos from multiple institutions including Brown University, University of Texas, and Skidmore College.