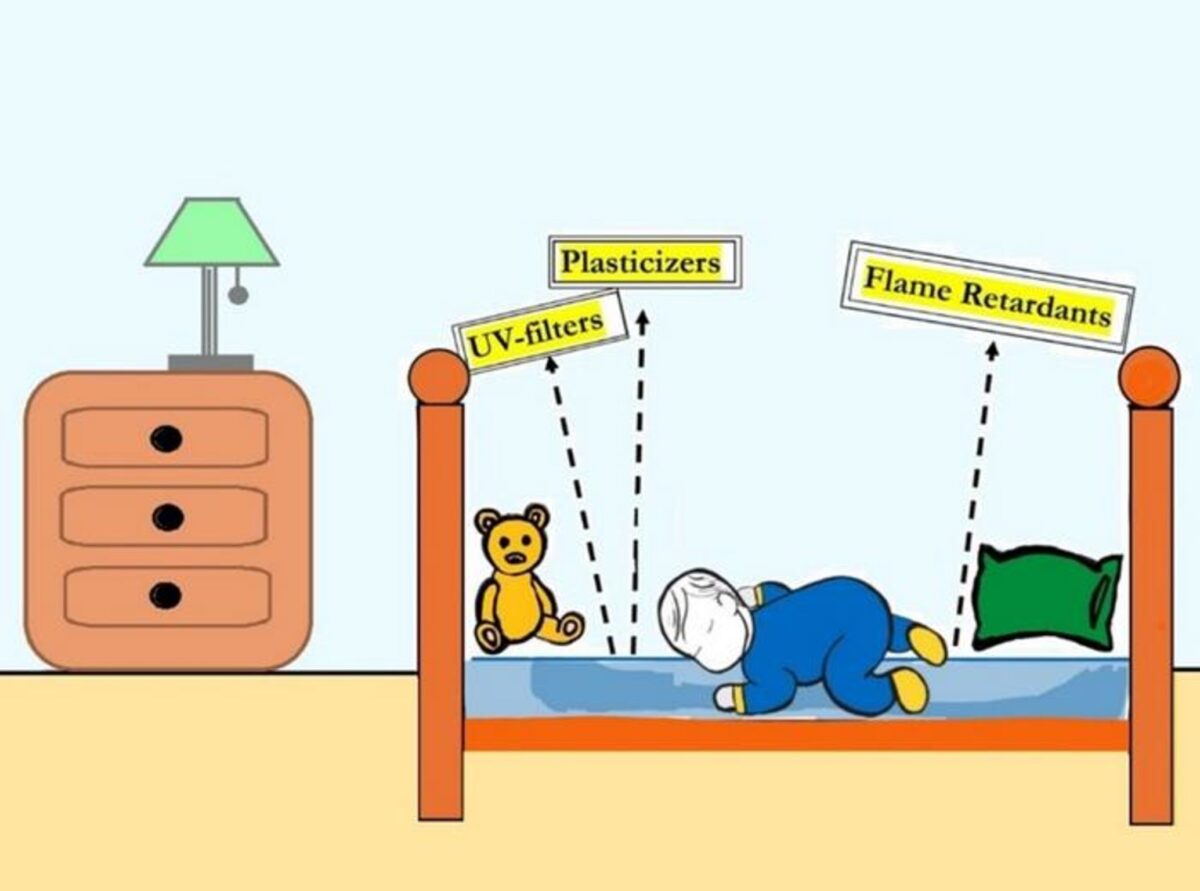

Children may be exposed to harmful chemicals seeping out of the mattresses they sleep on. (BaLL LunLa/Shutterstock)

In a nutshell

- Children’s mattresses can emit a range of harmful chemicals, including plasticizers, flame retardants, and UV filters, especially when exposed to body heat and weight during sleep.

- Some mattresses contained chemicals at levels that violate Canadian safety limits for children’s products, and even “eco-certified” models weren’t always free of restricted substances.

- Regulatory gaps leave parents with little protection or labeling guidance, meaning millions of children may be unknowingly exposed to chemicals linked to asthma, reduced IQ, and other developmental risks during sleep.

TORONTO — Your child’s mattress could be exposing them to a cocktail of harmful chemicals while they sleep. Alarming new research from the University of Toronto finds that children’s mattresses emit up to 21 different harmful compounds that increase dramatically when your child lays down for bedtime.

Research published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology reveals that children aged 1-4 years, who typically spend up to 18 hours a day in their beds, are being exposed to elevated levels of semivolatile organic compounds (SVOCs) that migrate from their mattresses into the air they breathe and onto their skin.

What’s worse, these chemicals, which include plasticizers, flame retardants, and UV filters, are released in significantly higher amounts when a child’s body heat and weight are applied to the mattress.

The research team found nearly two dozen different SVOCs across four chemical classes in the new children’s mattresses they tested. One mattress contained levels of di-n-butyl phthalate that exceeded Canadian regulations for children’s mattresses, while five others contained chemicals at concentrations that would violate regulations for children’s toys, though these same chemicals remain unregulated in mattresses.

This research raises troubling questions about regulatory gaps that allow potentially harmful chemicals in products where young children spend most of their developmental years.

The research team purchased 16 new children’s mattresses from major North American retailers, both online and in stores, priced between $50 and $105 CAD (about $36 to $76 USD). These represented medium to lower-priced options readily available to consumers. They tested foam and cover materials separately for 45 different target chemicals.

One mattress contained high levels of tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP), a flame retardant that has been prohibited from use in Canada since 2014. Five mattresses had between 1% and 3% of various organophosphate esters, chemicals used as flame retardants that have been linked to developmental issues.

“Parents should be able to lay their children down for sleep knowing they are safe and snug,” says co-author Arlene Blum, Executive Director of the Green Science Policy Institute, in a statement. “Flame retardants have a long history of harming our children’s cognitive function and ability to learn. It’s concerning that these chemicals are still being found in children’s mattresses even though we know they have no proven fire-safety benefit and aren’t needed to comply with flammability standards.”

The chemicals of concern fall into four main categories: phthalates (PAEs), which are plasticizers added to make materials more flexible; organophosphate esters (OPEs), used as flame retardants; benzophenones (BPs); and salicylates (SALs), which are UV filters used in fabric dyes and synthetic resins.

Researchers simulated real sleeping conditions. They didn’t just test what chemicals were in the mattresses; they measured what actually gets released under different conditions.

The researchers found that emissions increased dramatically under realistic sleeping conditions. At room temperature, only about a quarter of the target chemicals were released from the test mattresses. This number nearly doubled when the researchers applied body-temperature heat to the mattresses, and more chemicals emerged when both heat and weight were applied together, simulating a sleeping child.

This means that when a child lies on their mattress, their body heat and weight dramatically increase their exposure to these chemicals. The research team simulated this by heating sections of mattresses to 37.5°C (99.5°F) and applying 7.5 kg (16.5 pounds) of weight, roughly equivalent to the weight of a 6.5-month-old baby.

Many of these chemicals have been associated with concerning health effects in children. Growing scientific evidence links exposure to some SVOCs with increased rates of allergic diseases like childhood asthma, along with various neurodevelopmental impacts including effects on cognitive abilities, IQ scores, social behavior, and memory function.

Children are especially vulnerable because of their developing bodies and behaviors. Their breathing rates are about 10 times higher than adults, and their skin surface area relative to body weight is more than three times greater. They also have higher dermal permeability compared to adults and engage in more hand-to-mouth activities that can increase exposure.

The researchers found no relationship between the price of mattresses and the number or concentration of chemicals detected. Even certified “eco-friendly” mattresses weren’t necessarily safer, with one of two certified mattresses containing a prohibited chemical that violated the terms of its certification.

The study also revealed that mattress manufacturers appear to be changing formulations frequently. When researchers purchased “duplicate” mattresses of the same brand about two years apart, they found significant differences in their chemical composition, suggesting consumers can’t rely on past testing or reviews of specific brands.

Canada regulates certain phthalates in children’s products, including mattresses, limiting them to 0.1% by weight. However, the researchers found one mattress with 0.22% di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP), exceeding this limit. Several other mattresses contained chemicals at levels that would be prohibited in children’s toys but are unregulated in mattresses.

Significant gaps in regulations and manufacturer oversight leave vulnerable children exposed to a complex mixture of chemicals during the many hours they spend sleeping. With limited labeling requirements and the frequent reformulation of products, parents have few tools to make informed choices about safer mattress options.

Our homes, particularly our bedrooms, may harbor unexpected chemical exposures that could impact developing children. Until regulations catch up with the science, millions of children will continue sleeping on mattresses that silently release potentially harmful chemicals precisely when their growing bodies are most vulnerable.

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers tested 16 new children’s mattresses purchased from major North American retailers, priced from $50 to $105 CAD. They collected samples of foam and cover materials from each mattress and analyzed them for 45 different target chemicals including phthalates, organophosphate esters, benzophenones, and salicylates. To test emissions, they used silicone rubber (PDMS) passive samplers on mattresses under eight different conditions: at room temperature, with heat (37.5°C) to simulate body temperature, with weight (7.5 kg) to simulate a child’s body weight, and with both heat and weight applied. They also collected air samples from different heights above the mattresses. The polymer type of mattress covers was identified using FTIR spectroscopy. All samples were analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Results

Twenty-one out of 45 target chemicals were detected in the 16 mattresses. One mattress exceeded Canadian regulatory limits for di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP) at 0.22% by weight, while five had levels of other phthalates above 0.1% that would be prohibited in children’s toys but not mattresses. One mattress contained high levels of TCEP, a flame retardant prohibited in Canada since 2014. Five mattresses contained 1-3% of various organophosphate esters. The researchers found chemical emissions increased significantly when body temperature and weight were applied—only 12 chemicals were detected at room temperature, but this increased to 21 when both heat and weight were applied. UV-filters were detected in mattress covers, which is the first data of this kind for children’s mattresses. “Duplicate” mattresses of the same brand purchased two years apart showed different chemical compositions and concentrations.

Limitations

The study had a relatively small sample size of 16 mattresses. The researchers simulated rather than measured actual exposure in children. All mattresses tested were in the low-to-medium price range, so the findings might not apply to higher-end mattresses. The study focused on initial emissions from new mattresses and didn’t examine how chemical release might change over the lifetime of a mattress or account for effects of bedding or children’s clothing that might reduce exposure.

Funding and Disclosures

Funding was provided to the lead author by a University of Toronto Fellowship and Ontario Graduate Scholarship and by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant. The authors declared no competing financial interests. The study received assistance from various experts including Prof. Yael Dubowski (Technion University, Israel), Monika Smielowska (Gdańsk University of Technology, Poland), and others who provided advice on analytical methods and flammability standards.

Publication Information

The paper titled “Are Sleeping Children Exposed to Plasticizers, Flame Retardants, and UV-Filters from Their Mattresses?” was authored by Sara Vaezafshar, Sylvia Wolk, Kayla Simpson, Razegheh Akhbarizadeh, Arlene Blum, Liisa M. Jantunen, and Miriam L. Diamond and published in Environmental Science & Technology in March 2025.