Great white shark charges after a bait line. (Photo by Martin Prochazkacz on Shutterstock)

In a nutshell

- A new study finds that about 5% of shark bites in French Polynesia occurred after humans provoked the animals, typically by spearing, harpooning, or handling them.

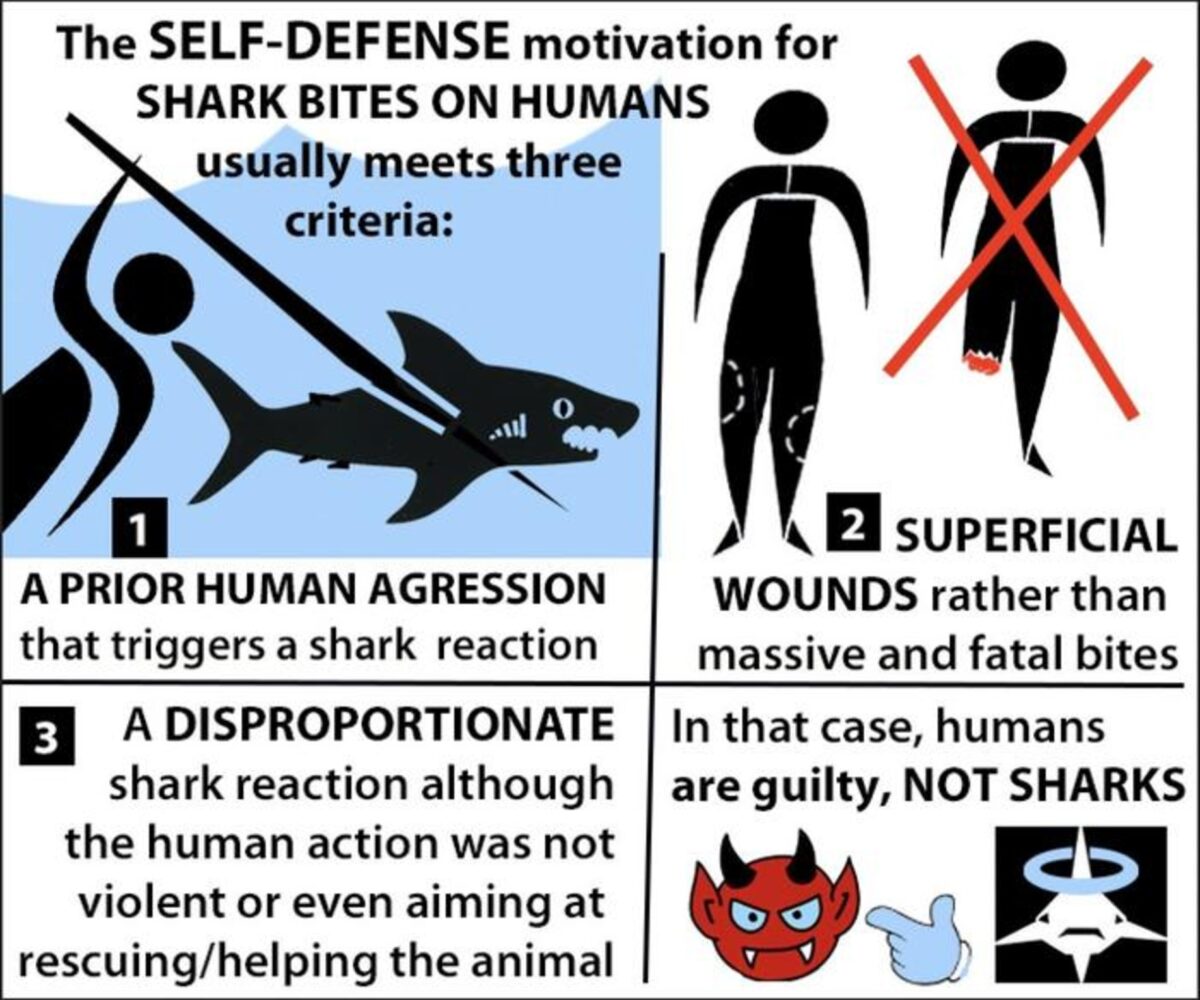

- Unlike predatory attacks, self-defense bites tend to be sudden, shallow, and non-lethal, delivered without warning displays and often meant to deter rather than kill.

- Researchers argue that sensationalized headlines obscure the human role in provoking bites, which harms shark conservation efforts and fuels unwarranted fear.

PARIS — The villain in “Jaws” might need a redemption arc. Surprising new research reveals that sharks aren’t the mindless attackers we’ve portrayed them as. Instead, many are simply defending themselves against human provocation. A multi-decade international study shows that when sharks bite after being speared, harpooned, or roughly handled, they typically deliver calculated, minimally damaging bites meant to deter rather than destroy.

If someone stabbed you with a spear or grabbed you around the neck, wouldn’t you fight back? Turns out sharks feel the same way.

According to the research published in Frontiers in Conservation Science, after a human acts aggressively toward a shark, the animal responds with immediate defensive aggression, creating a pattern of self-defense bites.

“These bites are simply a manifestation of survival instinct, and the responsibility for the incident needs to be reversed,” says study author Eric Clua, a shark specialist at Université PSL, in a statement.

The study reveals that approximately 5% of shark bites on humans occur after people provoke the animals first, whether by spearing them while fishing, harpooning them in traps, or handling them without proper care.

Most remarkably, these retaliatory bites rarely prove fatal. Unlike predatory attacks where sharks aim to eat their victims and remove significant flesh, defensive bites typically cause superficial wounds with minimal tearing. It’s as though the sharks are saying, “Back off!” rather than “You’re dinner.”

When Humans Cross the Line

Researchers documented 16 cases of apparent self-defense bites in French Polynesia between 1942 and 2023. These incidents primarily occurred during spearfishing (38%) or when fishermen were harpooning sharks trapped in traditional fishing devices (43%).

One particularly telling case from 2016 involved two Polynesian spearfishermen who encountered several gray reef sharks while fishing. When one shark approached, a fisherman shot it with a spear with the intention of merely frightening it away. The injured shark promptly bit the man’s calf, then his hand and wrist. When another fisherman tried to help, the shark bit him too. Both men required reconstructive surgery but survived.

“Some species of coastal shark, such as the gray reef shark, are both particularly territorial and bold enough to come to contact with humans,” says Clua.

Another revealing incident featured scientists attempting to safely handle a blacktip reef shark for research purposes. When one researcher improperly grabbed the shark behind its gills rather than near its head, it had enough room to bend backward and bite the scientist’s hand. The resulting wounds were superficial; just enough to communicate that the handling technique was incorrect.

The researchers caution that people should be aware that attacking sharks may trigger retaliatory bites, and emphasize that untrained individuals should never try to rescue distressed sharks, as the animals may bite indiscriminately in response.

Five shark species were implicated in these defensive bites: gray reef sharks (62.5%), sicklefin lemon sharks (12.5%), tawny nurse sharks (12.5%), blacktip reef sharks (6.25%), and whitetip reef sharks (6.25%). Notably absent from this list are the species most often associated with deadly attacks on humans—great whites, tigers, and bull sharks—possibly because their size and power deter humans from provoking them in the first place.

This is similar to patterns observed in other animals. Birds like cassowaries and mammals like brown bears also primarily attack humans when threatened or cornered, rather than as predators seeking prey.

How to Spot a Defensive Bite

What distinguishes these defensive bites from other shark bites? For one, they occur immediately after human aggression without warning displays like lowered pectoral fins or hunched swimming. They’re also often delivered repeatedly, yet still with minimal tissue removal compared to predatory attacks, which typically remove significant flesh and are more likely to be fatal.

There are also cases of antipredatory bites, where sharks bite in anticipation of human aggression before it occurs. Antipredatory bites typically follow warning displays, while self-defense bites happen after the shark has already been harmed or grabbed.

While this study focused on French Polynesia, where traditional fish traps and spearfishing are common, the researchers believe self-defense bites likely occur worldwide. Data from Australia shows that 49% of bites from wobbegong sharks, docile bottom-dwellers with blunt teeth, happen after people step on or get too close to them. Similarly, the Global Shark Attack File indicates that about 4.6% of all recorded shark bites worldwide might be motivated by self-defense.

The Media’s Role

In the media, shark bites are usually portrayed as aggressive. When a local newspaper ran headlines about the 2016 incident with the spearfishermen, every headline framed it as an “attack” by the shark on the humans, despite the humans having speared the shark first.

The media often sensationalizes defensive shark bites as attacks. More objective reporting of human responsibility in triggering these incidents could help improve public attitudes toward sharks and support conservation efforts.

“Do not interact physically with a shark, even if it appears harmless or is in distress. It may at any moment consider this to be an aggression and react accordingly,” says Clua. “These are potentially dangerous animals, and not touching them is not only wise, but also a sign of the respect we owe them.”

Sometimes we’re not the victims in shark-human interactions; we’re the aggressors. And like any creature with survival instincts, sharks aren’t afraid to remind us of that fact.

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers analyzed shark bites in French Polynesia over the past 60 years, categorizing them based on motivation. They specifically identified bites that followed human aggression toward sharks, classifying these as “self-defense” bites. From 2009 to 2023, they calculated the yearly prevalence of self-defense bites. The team also conducted detailed case studies, examining spearfishing incidents, traditional fishing trap use, and shark handling situations. They documented the context, bite characteristics, and shark species involved by interviewing victims, examining medical reports, and analyzing photographs of wounds.

Results

The study identified 16 shark bites between 1942 and 2023 that appeared motivated by self-defense after human aggression. These incidents primarily involved gray reef sharks (62.5%) and occurred during shark harpooning in fish traps (43%) or spearfishing (38%). Self-defense bites represented approximately 5% of all shark bites documented in French Polynesia from 2009-2023. These bites were characterized by being sudden, superficial, sometimes repetitive, and rarely fatal. They lacked the warning displays (like hunched swimming) seen before other types of shark bites and didn’t involve significant tissue removal like predatory bites.

Limitations

The study focused exclusively on French Polynesia, where specific fishing practices may create unique shark-human interactions not representative of global patterns. Data collection before 2009 was incomplete and less reliable. The researchers note that self-defense bites may be underreported because humans are reluctant to admit their role in provoking sharks. The sample size of 16 confirmed self-defense bites is relatively small, though the researchers supplemented this with global data indicating similar patterns elsewhere.

Funding and Disclosures

The study received funding from the French Government ANR-21-CE03-0004. Article processing charges were paid through financial support from Shark Mission France NGO and F. Rossier’s efforts. The research was conducted under a special permit issued by the Ministry of Culture and Environment of French Polynesia (ref: N°011492/MCE/ENV from October 16, 2019).

Publication Information

The paper “The Talion law ‘tooth for a tooth’: self-defense as a motivation for shark bites on human aggressors” was authored by Eric E.G. Clua, Thomas Vignaud, and Aaron J. Wirsing. It was published on April 25, 2025, in Frontiers in Conservation Science. The study is categorized as a Community Case Study and is available as an open-access article under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Use to swim with all types of sharks in the Marshall Islands. Learned that sharks sense through their teeth, and thus bite to determine what the object is. Humans are not their desired food. If they bite, do not struggle. They will let go(Btdt). Otherwise, if you are flailing about, like bears the sharks will bite down hard. And just like bears, if a shark is coming towards you, just stand your grounds, and get ready to punch noses.