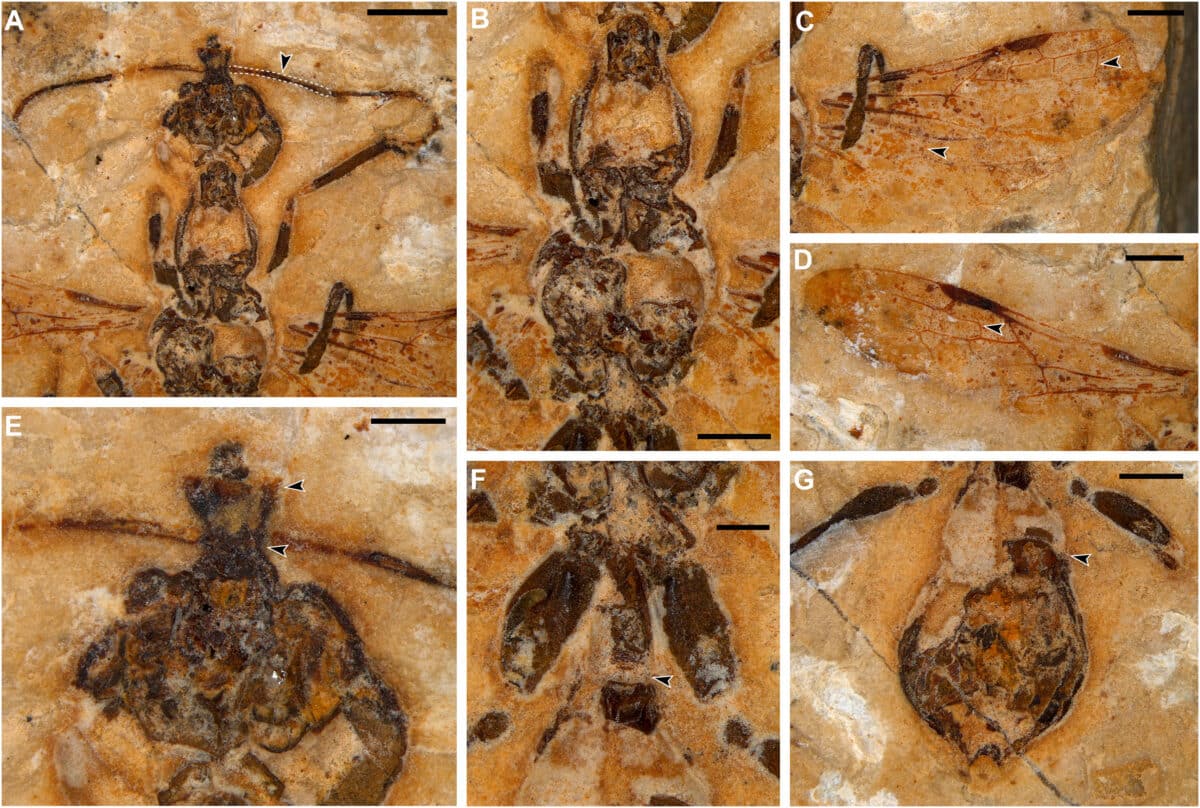

Vulcanidris cratensis fossil (Credit: Lepeco et al / Current Biology)

In a nutshell

- Scientists discovered the oldest known ant fossil (113 million years old) in Brazil, pushing back the confirmed timeline of ant evolution by 13 million years.

- The fossil belongs to extinct “hell ants” with unusual upward-pointing jaws, suggesting they had specialized hunting techniques different from modern ants.

- The discovery reveals hell ants lived in diverse environments across multiple continents, showing they were more widespread during the dinosaur era than previously thought.

SÃO PAOLO, Brazil — In the ancient landscapes of what is now northeastern Brazil, 113 million years ago, an unusual ant with bizarre upward-pointing jaws died and became entombed in limestone. This single fossil has just rewritten the timeline of ant evolution, pushing back their confirmed history by 13 million years.

Scientists have unearthed what they’re calling the oldest undisputed ant fossil ever discovered. The specimen belongs to an extinct group called “hell ants” — prehistoric predators sporting scythe-like mandibles that pointed skyward rather than forward like modern ants.

“This finding represents the earliest undisputed ant known to science,” states the research team in their paper published in Current Biology.

Bizarre Hunting Adaptations and Global Spread

The fossil, named Vulcanidris cratensis, shows these insects had already achieved a global presence much earlier than previously thought.

Before this finding, the oldest known ant fossils came from amber deposits in France and Myanmar dating back about 100 million years. This Brazilian specimen predates them significantly, suggesting ants were already widespread during the Early Cretaceous period when dinosaurs dominated the landscape.

Using advanced imaging technology called micro-CT scans (similar to a miniaturized version of medical CT scans), researchers examined the fossil’s anatomy in detail. The scans revealed jaws with tips that could contact the front plate of the head, forming a cavity likely used to trap prey.

The research team, led by Anderson Lepeco from the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, found that this specimen was closely related to hell ant species previously discovered in Burmese amber. This connection reinforces the idea that these ancient ants could spread between continents during the Cretaceous period.

Thriving in Diverse Environments

Unlike previous hell ant fossils found in ancient amber formed in humid, forested regions, this Brazilian specimen lived in a drastically different habitat. The Crato Formation where it was discovered points to a seasonal, semi-arid environment — essentially a shallow wetland within a broader dry landscape.

This environmental flexibility reveals these specialized predatory ants could thrive across dramatically different habitats worldwide.

According to the research paper, “Hell ants exhibited a wide ecological range, occurring in remarkably different environments throughout the globe.”

Evolutionary Dead End

Modern ants are ecological powerhouses, with over 14,000 known species shaping ecosystems globally. However, their rise to dominance wasn’t immediate. Fossil evidence indicates early ant groups like the hell ants were diverse during the Cretaceous, but the major ant lineages we know today evolved later and exploded in diversity after the extinction event that killed the dinosaurs.

The new fossil helps bridge the gap between ants and their wasp ancestors, showing how early these insects established themselves as key players in terrestrial ecosystems. Despite their early success, hell ants ultimately disappeared without leaving any descendants. Like many specialized Cretaceous animals, they vanished during the mass extinction at the end of the period.

This remarkable fossil doesn’t just push back the timeline of ant evolution — it offers a glimpse into a lost world where strange, scythe-jawed insects hunted across ancient landscapes long before humans would ever notice the tiny creatures building colonies in their gardens.

Paper Summary

Methodology

Researchers studied a fossil specimen (MZSP-CRA-0002) from the Crato Formation in northeastern Brazil, which dates to the Aptian stage of the Lower Cretaceous period, approximately 113 million years ago. The specimen was examined using standard microscopy techniques and photographed at multiple focus levels using a Leica DFC 295 camera attached to a stereomicroscope. The fossil was also analyzed using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) to visualize internal structures and create three-dimensional reconstructions. The team used these detailed examinations to identify key anatomical features and compare them with other known ant fossils. They conducted a phylogenetic analysis using MrBayes software to determine the fossil’s place in ant evolutionary history.

Results

The analysis confirmed that the specimen represents a new genus and species of hell ant (subfamily Haidomyrmecinae), which the researchers named Vulcanidris cratensis. Key diagnostic features included unusual mandibles that articulated ventrally on the head, a facial projection, and specialized predatory adaptations. The fossil’s age (113 million years) makes it the oldest undisputed ant known to science, predating previous records from France and Myanmar by at least 13 million years. The study revealed that Vulcanidris cratensis is closely related to hell ants found in Burmese amber, suggesting these ants were widespread and dispersed between continents. Their presence in Brazil also represents the first confirmed record of Haidomyrmecinae in western Gondwana, expanding understanding of early ant biogeography.

Limitations

While the fossil provides significant insights into early ant evolution, it represents a single specimen, which limits comprehensive understanding of variation within the species. The fossilization process also means some anatomical details are not perfectly preserved. Additionally, as with all paleontological studies, the fossil record is inherently incomplete, meaning there’s limited context for understanding the full ecological role and behaviors of these extinct insects. The researchers also note that another purported early ant fossil from the same region (Cariridris bipetiolata) remains controversial and inaccessible for re-examination, preventing comparison with the new specimen.

Funding/Disclosures

The research was supported by grants from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), including grants 2023/12809-0, 2022/12632-0, 2018/09666-5, 2019/09215-6, and 2021/07258-0. No competing interests were declared by the authors.

Publication Information

The study “A hell ant from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil” was published in Current Biology (Volume 35, pages 1-8) on May 5, 2025. The authors include Anderson Lepeco, Odair M. Meira, Diego M. Matielo, Carlos R.F. Brandão, and Gabriela P. Camacho, primarily affiliated with the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo and the Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil.